There’s a shift happening in earthquake science, and it’s not just in the tectonic plates. Results of a new five-year study reveal that the way experts model potential earthquakes is changing for good.

Experts behind the CyberShake project say they have identified a far more accurate and localized method of simulating earthquakes’ effects at specific locations. Based on the new models, LA is expected to see 10 to 50 percent more shaking across all magnitudes of earthquakes than previous models suggested.

The results have major implications for LA’s skyscrapers—and the future of building safety.

“We can’t predict earthquakes,” says Tom Jordan, a professor of geological sciences at USC and lead author of CyberShake. “But what we’re doing is a much better job of predicting what will happen when they occur.”

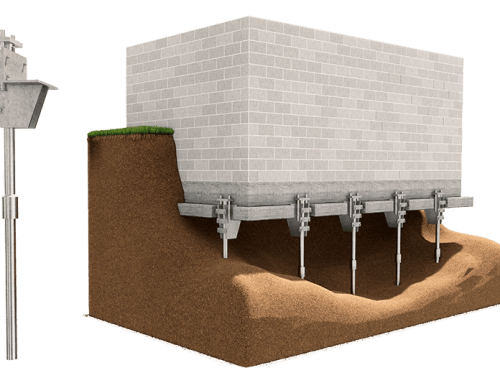

Developers and builders will have to reassess the security of “tall structures” in the aftermath of CyberShake’s findings— what specialists call 20-story buildings or more. According to John Vidale, director of the Southern California Earthquake Center, who run the survey, they will also have to find out how to construct stronger buildings in the future.

Approximately 14,000 buildings, including apartment buildings, were identified in 2014 at risk of collapse in a major earthquake. Scientists at UCLA have also launched a program to expand earthquake-resistant design for individual skyscrapers and earthquake-resistant design for entire communities.

And city law now requires tall buildings to be equipped with earthquake data-gathering tools.

In the decades leading up to CyberShake, scientists relied on retroactive models called Ground Motion Prediction Equations or GMPEs. These equations are divided into historical records of quakes from around the world.

CyberShake, which was launched in response to data showing that the Los Angeles Basin was moving differently from the previous calculations predicted, revealed that past methods resulted not only in very broad estimates, but also in largely incorrect ones. It relies instead on local conditions and existing geology.

“We’re shifting from thinking about how dangerous the quakes are by looking at past records, to calculating what the next ones will look like based on geology,” says Vidale.

“Instead of going to the track record, we’re looking at the physics of where we are and what’s coming next,” he says.

Historically, GMPEs have been used as the basis for building code design. But now, with CyberShake’s technology, its authors say that engineers can pair predictive seismograms with structural simulations to better design buildings. These are particularly important civic facilities, such as hospitals, dams and power stations.

It is also possible that, using CyberShake technology, engineers will be able to locate a building plan tailored to the seismic hazards specific to the proposed site.

New models also show that some geographical regions are more dangerous than previously thought. Those in large basins, such as LA and Mexico City, are particularly at risk because the ground is soft and deep, so much so that experts often compare the shake with the jiggling of the Jell-O bowl.

“In some areas of Los Angeles County, such as Century City, Culver City, Long Beach or Santa Monica, the new projections almost double the previous estimate of the type of ground shaking that is most threatening to a tall building,” according to the New York Times.

However, experts are quick to remind us that estimates are not guarantees.

“It doesn’t mean that the ground moves are going to be super high at all locations,” says Christine Goulet, co-authorand developer of CyberShake, Curbed. “It may increase the risk, effectively, but we don’t know how much.” That might mean that there will be more windowless skyscrapers in LA’s future. The strength of the building is determined by factors such as how much steel is used and how many open spaces and windows it has. Buildings with open spaces, such as atriums and open roadways, are much weaker in the event of an earthquake.

Moving forward, engineers and city officials will have to work together on how to implement these new predictions into safer building codes. But because building codes change every six years, there are many buildings in LA that are technically sound, but structurally sound, according to Goulet. Landlords and developers will have to decide whether to reinforce those buildings that were considered earthquake-safe as far back as the 1930s.

“People need to realize that codes are evolving over time,” Goulet warned. “As a society, we’re going to have to make choices.” Choices, Goulet says, about what era code should be used as a safety standard.

Seattle is one of the first cities to make that choice. It has announced that it will start using new CyberShake maps to determine building codes starting on December 1.

For now, engineers and scientists like Goulet are waiting in LA to hear when the new models will be taken into account.

“We’ve got to incorporate it,” said Jim Malley, a structural engineer and co-organizer of the conference to the New York Times. “We haven’t decided how to do that.”