A young teacher named Stephen Anaya and his family moved to a shingle-style bungalow in the early 20th century on Fraser Avenue’s historic beach side street in Santa Monica in 1974. They bought it five years later. “Living on the street has been our dream,” he says. “Buying the worst house on the street and fixing it was our philosophy. That’s the only way we could do it. “The wood-frame cottage had been through several lives, measuring 25 by 95 feet. A carpenter named Max Demme, a fugitive from the Austro-Hungarian empire, owned it for decades. During the depression, Demme used an overabundance of nails to keep the aging cottage together as best he could. The Anayas would lovingly bring their seaside home up to code throughout the 1980s, retaining one of the best examples of humble beachside architecture in Southern California, far from the lavish multi-floor mansions that line the coast today.

The early days of beachfront living sound too good to be true in the age of multi-million-dollar beach homes — out of reach to all but the richest of Angelenos.

Early beach homes are built from telephone poles across the shores of the Southland and the wood from old piers. According to The Cottages and Castles of Laguna, architect Thomas Harper, who designed the first cottage in Laguna in 1883, used wood from abandoned boats.

According to Nina Fresco, a member of the board of Santa Monica, vacationers began to set up simple tents on the north and south beaches of Santa Monica in the 1870s and’ 80s. Although North Beach’s owners dealt harshly with commercial squatters, they were generally tolerant of “tenters” who would set up Palisades Park bluffs from the sea.

A modern angular house looming over an old little home with a slanting roofline and gray stucco and wood façade.

Today, Santa Monica’s average home is 2,993 square feet.

“The tents were like platforms with a frame and canvas walls in those days,” says Fresco. “Some people were even going to build small, really inexpensive, simple wooden shacks that were really one step up from the tents.” The forces quickly learned that tenters were really good for business. “People didn’t care that much because they didn’t compete with bath houses— they’d just hang out and rent bath suits from the bath houses,” says Fresco. “At the beginning of the summer season, the hardware stores would announce that they had a whole new stock of tents that people could buy.” When the grand Arcadia Hotel opened in 1887, investors quickly pounced on this newly fashionable beachfront town. Small lots were subdivided next to the resort, and developers built “slightly more commodious shacks” rented to holidaymakers, many from the East and Midwest. Wealthy lawyers and politicians built large holiday cottages on the bluffs around Strand Road.

Long-term land battles in the Ocean Park area that had stopped construction finally came to an end around 1900. Real estate agent Alexander Fraser, who advised developer George Hart (owner of Downtown LA’s Rosslyn Hotel), decided to bring some order to construction on the beachside.

“He’s like, all right, we’re getting all the shacks out of here, and we’re going to put restrictions on deeds and people have to build houses that cost a certain amount of money, and they’ve had requirements for construction,” says Fresco. “It was necessary to set them back, to have porches. And those houses are immediately selling like gangbusters.

Today, Fraser Avenue has the most clustered community of historic beach cottages in Santa Monica, one of the four remaining streets with intact original houses from the development. But the cottages and neighbourhoods were dramatically altered during World War II.

“We’ve bought our single-family home,” says Anaya. “But as most of the houses were, it was made into multiple units for the Douglas World War II aircraft staff. So, some of the houses were built up. Some of the rooms are bisected. The toilets are shared. That was to promote the jobs for the war effort throughout the area.

Half of the area was demolished in the 1950s to build high-rise condos. Fraser Avenue was a rundown, bohemian neighborhood by the time the Anayas moved in, dominated by people working in the music industry.

“In the 1970s, it was pretty funky,” says Anaya. It could also be dangerous, and there was constant vandalization and burning of the nearby Ocean Park Pier. Slowly but surely the Anayas lovingly restored their house, fixing the renovation of the handicraft of former owner Demme and the war years alterations. “In the 1980s, we really had to work hard to get it to code,” he says.

The shotgun essence of beach cottages in the early 20th century and their often-slapdash upkeep throughout the Southland is clear.

“We have a member who once told me they purchased one of these houses with their husband as newlyweds in the 1940s, and as she went to hang up their wedding photo, the nail went outside right through the wall,” says Jamie Erickson, curator of the Hermosa Beach Historical Society’s museum.

Even with the sea in mind, not all early beach dwellings were built. Holidaymakers would hunker down in “skid houses” in Hermosa Beach, small wood-frame structures built to house workers by oil companies.

“Some people bought them, and they carried them down to the beach here, and in the summer they would bring them by mule right to the seashore, and in the winter they would pull them back,” says long-time resident and contractor Rick Koenig. “It’s not much more than an ice-fishing shack.” Koenig spent his life restoring and improving historic beach cottages in and around Hermosa Beach. Reinforcing walls, unblocking and repairing cast-iron water pipes, redoing wooden floors and molding, undoing children’s damage to skateboards— it’s all in a day’s work for Koenig, whose family arrived in Hermosa in 1897. He’s also been working on his own home, a three-story beach cottage on Manhattan Avenue and 18th Street gingerbread-style, built by his grandfather on a lot costing just $400.

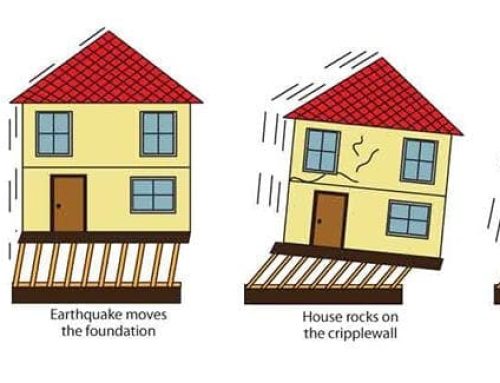

“We did not have many of the things we take for granted today in 1917, such as isolation, climate stripping, and codes for construction. When this site was built, there was no building department, “he says. “I have to admit that my grandfather was a great advocate of nature dancing. You switch with it when there’s an earthquake. They have their creaks and cracks, as with all these old places. But that’s part of the charm. “By the 1920s, homeowners and builders were completely caught up in the craze of the beach cottage. Hollywood Beach has been opened by developers in Ventura, selling 520 cottage-ready lots for as little as $200. Tiny, kitschy beach cottages with distinctive double doors rose up on Balboa Island, while the film producer Harry Greene built a tiny complex of cottages in Laguna. Even the Rindge insular family got into the act, opening up a small portion of their large Malibu holdings to establish what would become the popular “movie colony.” Stars like Bing Crosby and Constance Bennett would occupy this seasonal resort of 100 temporary beach shacks.

Crystal Cove State Park in Orange County, just off Pacific Coast Highway, is certainly the best-preserved example of these 1920s beach shack towns. Over 30 restored, brightly colored wooden beach shacks are still hugging the shore, putting every guest in a laid-back mood instantly. These ramshackle buildings are the culmination of decades of work, often by the same families who started as squatters on the beachfront land owned by the Irvine Company in the early 20th century.

The Ester Buhne schooner wrecked off the coast in 1927, proving a blessing to these novice builders who used the lumber that washed ashore to make simple beach shacks. Over the years, “coveites” would return year after year to their second homes, adding to their uninsulated shacks until they became large-scale, rambling houses.

But an influx of money and technological developments during the 1920s and 1930s would also signify the eventual death knell for the traditional beach cottage with a wood frame. As Elizabeth McMillian states in Beach House: the rich and famous began throwing their money around from Malibu to Laguna, changing the beach retreat idea. Architects of such great names as Stiles O.

Today, Santa Monica’s average home is 2,993 square feet, costing over $1.6 million. Yet life is still easy and pleasant for those fortunate enough to live in the Southland’s remaining beach cottages.

“It’s a wonderful place to live,” Anaya says of his cottage on Fraser Avenue in Santa Monica, where homes now sell for upward of $4 million.

“We’ve got a nice youth and old mix,” he says. “We’ve had an annual July Fourth and Independence Day parade, and it’s been going on since 1971. That’s where everybody dresses up, and the street is closed, and banners are put up. And there are not enough people to see it often. So they take turns. One group goes down the street and the others are the spectators, and vice versa.” For Koenig, Hermosa is his “Mayberry by the sea.” His historic house, now worth well more than $1 million, is a connection to his family—past, present, and future. “Some people believe in ghosts, some people don’t, but I feel like there have been six generations in this house, including my grandchildren, and I can sense my grandmother, my mother, and things here,” he says. “It’s a kind of Westernized feng shui, very comforting.”